Tasmania’s robbins island wind farm gets the green light—but can it keep the orange-bellied parrot safe?

Australia has approved one of its most hotly debated renewable energy projects: the 900 MW Robbins Island wind farm in north-west Tasmania. Environment Minister Murray Watt signed off on the ACEN Australia project with a raft of conditions—88 in total—aimed at protecting wildlife, including the critically endangered orange-bellied parrot. The stakes are high on both sides. On climate and energy, the federal government and Tasmania say the project will power about 422,000 homes and cut 3.4 million tonnes of CO₂ annually—roughly like removing more than one million cars from the road. On jobs, the state says the decision finally brings “certainty,” unlocking hundreds of regional roles. On biodiversity, the flashpoint is the orange-bellied parrot (Neophema chrysogaster)—one of the world’s rarest parrots and listed as Critically Endangered. This small migrant breeds in Tasmania and winters on Australia’s southeast mainland, flying across Bass Strait twice a year. Conservation scientists and bird groups argue Robbins Island sits in a high-risk corridor for that migration. Earlier in 2025, new tracking and field data were presented that the birds’ path crosses the site, sharpening calls to block or heavily modify the proposal. Watt’s approval attempts to thread that needle. Conditions include three years of pre-construction bird surveys, a dedicated conservation fund for the orange-bellied parrot, and requirements to protect other sensitive species—such as buffers around Tasmanian wedge-tailed eagle nests and measures for the disease-free Tasmanian devil population on the island. Regulators also flagged turbine curtailment (shutdowns) during high-risk periods as a possible safeguard. Critics remain unconvinced. BirdLife Australia has long described Robbins Island as Tasmania’s most crucial shorebird site and warns that placing up to 100 turbines in the area could undermine recovery work for the parrot and other birds. The Bob Brown Foundation likewise argues the island is a “biodiversity ark,” citing risks to migratory shorebirds, raptors and a devil population free of facial tumour disease. Supporters counter that the climate benefits are significant and that strict, enforceable conditions—and real-time monitoring—can keep risks acceptably low. Two practical caveats will shape what happens next. First, the project still needs approvals for a ~120 km transmission line to connect Robbins Island to the grid near Hampshire, so timelines will hinge on that separate process. Second, the conditions place surveys, buffers and adaptive management front-and-centre; if monitoring shows unacceptable collision or disturbance risk—especially during the parrots’ autumn and spring crossings—operational curtailment will be on the table. What to watch: • Migration windows. The parrot typically moves between late spring and autumn; credible detections near turbine strings during those windows would trigger the toughest tests of the approval. • Independent science. Transparent telemetry, radar and carcass-search protocols will matter as much as raw turbine counts. The approval’s value lives or dies on monitoring design and public reporting. • Transmission route. The grid link decision could reshape habitat impacts off the island—and ultimately determine when (or whether) the project delivers power at scale.

Photos and Videos

Explore More

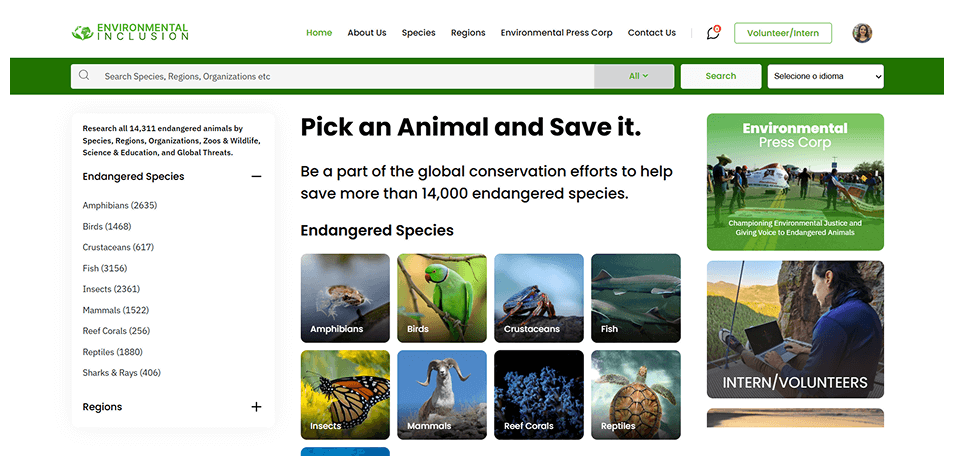

To read more about this species and 14,000 other species around the world come to our website, register and explore more courageous stories like this one.

Pick an Animal and Save It